'Spinning Mule' or the invention of the textile industry

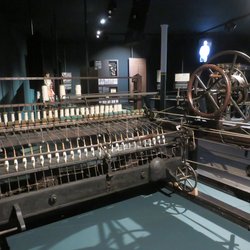

In 1764 the English weaver James Hargreaves designs the "Spinning Jenny" - the first spinning machine ever built. Thanks to its ingenious mechanics, a single worker can initially operate eight and later dozens of spindles at the same time - thus putting just as many spinners and their spinning wheels out of work. The competing "Waterframe", also developed in 1764 by the English wigmaker Richard Arkwright, is water-powered and part of the world's first industrial cotton spinning mill in Cromford since 1771. Yet the machine that is most widely used for the next 100 years is Samuel Crompton's 'Spinning Mule' of 1779, a kind of hybrid between Spinning Jenny and Waterframe, featuring a semi-automatic carriage with up to 500 rotating spindles that twist the roving into yarn as the carriage is pulled out and wind it onto bobbins as it travels back in. The only surviving spinning mule, probably designed by Samuel Crompton himself, is kept in the Bolton Museum & Art Gallery.

Worried for their jobs, spinners and weavers repeatedly rage against the new machines. But the automation of the textile industry has become irreversible.

To defend its technological lead, the English government bans technology exports on death penalty as early as 1774 and strictly forbids skilled workers from leaving the country. This is not entirely effective. One of those who successfully evade the restrictions is the Belgian entrepreneur Lieven Bauwens: in 1797/98 he smuggles a spinning mule onto the continent in order to replicate it in several factories in Ghent and its surroundings. One of these machines is now on display in the Ghent Museum of Industry and marks the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in Flanders.