ON THE HISTORY OF COMMUNICATION

The final phase of industrialisation witnessed a revolution in communications: circulation figures for newspapers reached hitherto unknown heights, people were able to communicate directly across oceans and mountains, and photography became the first mass reproducible art form. The initial wave of changes affected the traditional medium of paper. Towards the end of the 18th century demand for paper had risen to such an extent that it could no longer be met by manual production. In 1799 a Frenchman by the name of Nicolas-Louis Robert invented the first papermaking machine. His solution took the form of a continuous screen moving like an endless belt between two rollers. It was stretched across a barrel to catch the watery pulp and produce a continuous strip of paper instead of individual sheets. This was the start of unbroken production. In the following years a British engineer by the name of Bryan Donkin improved the machine by drying the long strip of paper between steam heated cylinders, smoothing it out and winding it into rolls.

Now the traditional raw material used in papermaking – cotton rags – proved insufficient to meet demand. Around the middle of the 19th century a weaver from Saxony named Friedrich Gottlob Keller discovered that it was also possible to process wood to paper pulp by grinding it down mechanically into fibres. In 1854 Charles Watt und Hugh Burgess 1854 developed a soda process to produce smooth and more durable fibres chemically: they boiled up wood and added sulphur to produce cellulose. Unfortunately the chemicals used in the process made the paper industry the second greatest polluter of the environment in the 19th century, after the textile industry.

Modern methods of printing received a decisive boost with the introduction of the high-speed printing press by the German book printer, Friedrich Koenig. Instead of using a flat platen press, a rotating cylinder was used to push down the roll of paper against a flat inking table. This was the process used in London to produce the first copy of the Times in 1814. Since printing could now be done more quickly, newspapers were more up-to-date and circulation rose. The principle was further improved by the introduction of the rotary printing press in America by Richard Hoe, an invention which he patented in 1845. He succeeded in producing a printing press in which a curved cylindrical impression was run between two cylinders. It was not long before long continuous rolls of paper were introduced. This enabled newspapers to be printed in a single continual conveyor belt process.

Now the only hurdle left was the problem of setting the type, which was traditionally done by hand. This was solved in the USA in 1884 by a watchmaker named Ottmar Mergenthaler whose Lynotype machine revolutionised the art of printing by using a keyboard to create an entire line of metal matrices at once. Once these were assembled, the machine forced a molten lead alloy into a mould sandwiched between the molten metal pot and the line of matrices, which were then returned to the proper channels in the magazine in preparation for their next usage. This process produced a complete line of type in reverse, so it would read properly when used to transfer ink onto paper. The completed slugs (lines of type) were then assembled into a page "form" that was placed in the printing press. The word linotype, by the way, derives from the phrase "line of type". Newspaper sales were incredibly high especially in the most important mass market, the USA.

Around the end of the 19th century the revolution in the newspaper industry received a further boost from the invention of photography. People had known for a long time that it was possible to produce an image with a lens. It was also known that light can affect certain substances. But it was not until 1827 that a French teacher by the name of Nicéphore Niépce succeeded in creating the first durable image. Later Louis Daguerre improved photography by exposing a sensitive silver-coated copper plate to the light for several minutes. But the decisive step to making photography a mass medium - reproduction - was taken by the Englishman, William Talbot Fox, who developed a blueprint process which enabled prints to be taken from a single negative. Finally, in the 1890s, the American George Eastman invented celluloid roll film, and it was not long before the Eastman-Kodak company began to market box cameras to the general public.

The electrical telegraph opened up a new dimension in communications. Since the start of the 19th century dozens of inventors had been experimenting with sending news via weak electric wires over long distances and in real time. But in order to make this practicable people had to be able to understand the nature of electricity better, especially the connection between electric current and magnetism. In 1837 two Englishmen by the name of Wheatstone and Cooke patented the first electromagnetic telegraph and put it into use for railway traffic. The receiver contained a dial with the letters of the alphabet arranged upon it. To send a message, magnetic needles were turned towards the desired letters. The magnetism induced an electric current which was then sent through several wire circuits to another receiver. The current set the magnetic needles on the second receiver in motion, and these then pointed to the same letters which had been typed in by the sender.

In the same year in the USA, an amateur researcher by the name of Samuel Morse used an alternative system that only required a single wire line. In order to broadcast a message, the information was first coded into two different impulses, short and long: dots and dashes. This simple telegraph alphabet soon established itself, not least because Morse was able to deliver a new receiver which automatically recorded the messages on a moving strip of paper. A worldwide telegraph network was subsequently established on a basis similar to the binary code: an early form of the internet.

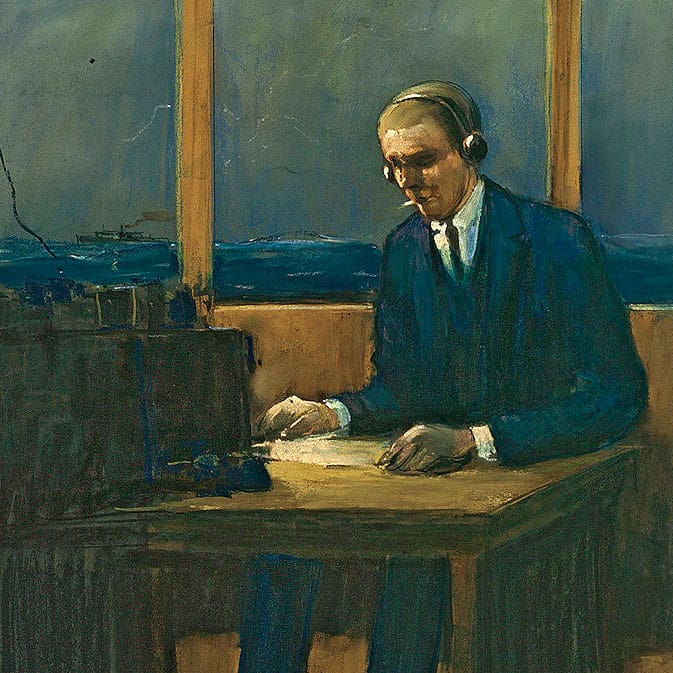

A thousand kilometres of telegraph wire had already been laid – including under the ocean – when Guglielmo Marconi gave the first demonstration of wireless telegraphy. In the apparatus he made in 1896, jumping sparks produced electromagnetic waves which transmitted sounds and speech way beyond visible distances. With the aid of ever higher antennae people were able to cover increasingly large distances. Later people learnt how to exploit the influence of wave frequencies on broadcasting. Short wave transmitters, for example, enabled people to communicate with far-off ships at sea – one of the advantages of wireless telegraphy. Today radio, television and mobile telephones work on the same principle.

At first only a very few people recognised the commercial potential of the telephone. In 1861, a German, Philipp Reis, was the first person to succeed in transmitting voices and sound electrically. But the commercial exploitation of voice communications only began with the telephone that Alexander Graham Bell, a professor of vocal physiology and elocution, presented to the American public in 1876. Here one person spoke into an apparatus consisting essentially of a thin membrane carrying a light stylus. The membrane was vibrated by the voice and the stylus traced an undulating line on a plate of smoked glass. The line was a graphic representation of the vibrations of the membrane and the waves of sound in the air. A second membrane device was used to receive the signals and transform them back into the spoken word. It was not long before the membrane devices were replaced by carbon microphones. Copper was used for the telephone lines, and around the turn of the 20th century developments in telephone engineering began a triumphant march that was to continue into the 21st century.