ON THE INDUSTRIAL HISTORY OF CROATIA

For centuries, Croatia was squeezed between the expansionist Ottoman Empire in the southern Balkans, their rival, the Habsburg Empire, in the north and the Kingdom of Hungary to the east. Only the merchants of the medieval city of Ragusa, today Dubrovnik, largely succeeded in preserving their independence by adroitly playing the great powers off against each other. Their merchant ships competed with Venice in the Mediterranean, while their caravans sojourned across the Balkans to Istanbul. The city managed to retain its special position until the Atlantic became the focus of long-distance trade in the 16th century.

At this time, Hungary, whose monarch also ruled as King of Croatia, fell under the dominion of the Habsburgs. However, the rulers in Vienna used the Hungarian lands primarily as a source of agricultural products – and Croatia was among its remotest regions. Thus, industrialisation was inconceivable in the 19th century on account of the underdeveloped agricultural sector and an acute shortage of capital. Wood-working was the most highly developed industry, particularly the construction of ocean-going ships in the Adriatic port of Rijeka and inland vessels in Sisak and Vukovar. Osijek developed into a centre for silk production.

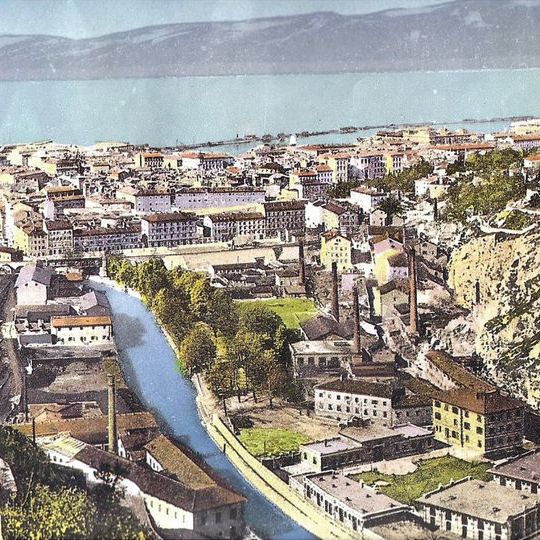

The halting expansion of the railways was governed either by Viennese interests or the desires of Budapest. For instance, in 1862 the gradually flourishing city of Zagreb was connected to the Austrian Southern Railway, linking it to the Austrian trading port of Trieste – and that city immediately appropriated Rijeka’s trade. Hungary connected Rijeka to a line to Budapest as compensation, but no one was interested in a railway through the interior. At any rate, the locomotive factory TŽV Gredelj was founded in Zagreb at the end of the century.

When the “Kingdom of Serbia, Croatia and Slovenia” was proclaimed after the dissolution of Austria-Hungary in 1918, Croatia and Slovenia were the most highly industrialised regions, benefited most from the domestic market within the new borders and attracted the greatest foreign investment. Important factories such as the Pliva chemical works and the electrical company Končar in Zagreb and the Đuro Đaković rail car factory in Slavonski Brod were established at virtually the same time. The country, however, soon rechristened the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, remained a crisis-plagued agrarian country.

Sweeping change occurred following the Second World War. As in the Eastern European “brother states”, socialist Yugoslavia’s government commenced an all-out expansion of heavy industry: oil and gas extraction, machinery, chemicals and transport had the highest priority, mining and metal processing expanded as well, and even the traditional industries of food production, wood processing and paper manufacturing grew dramatically. In particular, Croatia’s tradition-rich ship-building industry boomed in the shipyards of Rijeka, Pula and Split. The petrochemical industry was established on the Adriatic island of Krk. The petroleum company INA, founded in Zagreb, built a nation-wide network of petrol stations. At the same time, infrastructure was upgraded: hydroelectric plants were built in the valleys of the country’s rugged, mountainous outback. The first section of the highly symbolic “Highway No. 1” between Belgrade and Zagreb was opened in 1950 – though it soon acquired an ominous reputation as the “Autoput”. Construction of the Adria Magistral followed in the 1960s and 1970s, extending from Koper, Slovenia, along the entire Croatian coast to Dubrovnik.

Although President Tito’s break with Stalin in 1948 triggered an economic blockade by the Eastern Block, by the mid-1960s industry was posting spectacular growth rates and coming to dominate Yugoslavia’s economy. Concurrently, the government attempted to compensate for the disadvantages of a centrally controlled planned economy through a flexible policy they called the “Third Way”. As early as the start of the 1950s, it began channelling more investment into the production of consumer goods in response to the miserable supply situation. This was followed by experiments in greater autonomy for producers and a limited opening of the market, but by the time Tito died in 1980, the economy was still suffering under weaknesses similar to the orthodoxly governed socialist countries: overexploitation of resources, low productivity and a trade deficit with rapidly mushrooming foreign debt.

Croatia was part of the 'Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia', which disintegrated since 1991.

Therefore, for completeness, please also read our articles on the industrial history of the other states that were formerly part of Yugoslavia.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Kosovo

Montenegro

North Macedonia

Serbia

Slovenia