ON THE INDUSTRIAL HISTORY OF LUXEMBOURG

Who would have thought that this small country in the heart of Europe was once one of the largest iron producers in the world? Whereas the north of Luxemburg is mostly agricultural, industrial history has left its traces in the south. Long before the country's capital became a leading financial and administrative centre there were textile factories on the banks of the River Alzette. As so often these were the forerunners of industrialisation.

In 1828 the Godchaux brothers set up a cloth-making factory on the edge of the town. At first it was powered by a water wheel; later with the addition of a steam engine. A spinning mill was also set up in the Esch Valley, whose looms were driven by a water turbine. Godchaux expanded, set up subsidiary factories at home and abroad and marketed its products in Europe and overseas. By now the suburb where the factory was located had its own housing estate for the workers, a kindergarten and the director’s villa. It even had its own electricity works at a time when the town of Luxemburg was still lit by gas.

The porcelain manufacturer Villeroy und Boch is a prime example of the cross-border history in the three country area of the Saarland, Lorraine and Luxemburg. It was first set up in Lorraine by Jean-Francois Boch in 1748, and soon the business began an early form of serial production in Luxemburg. In Saarland, on the other hand, Nicolas Villeroy had developed a new process for printing complicated decorations on porcelain. At the beginning of the 19th century the Boch company opened a highly modern and almost completely mechanised factory in Mettlach on the Saar. In 1836 the two firms merged, thereby laying the foundations for the present-day concern.

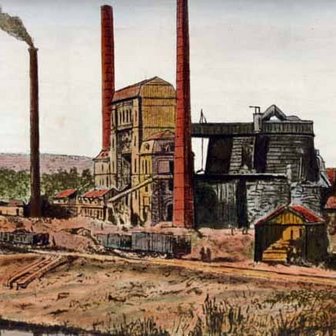

The whole of Luxemburg's economy profited from the fact that the country entered the German Customs Union in 1842. The road network was extended, two railway companies were set up and new industrial businesses expanded. In 1837 Auguste Metz erected an ironworks on the site of an oil and flour mill in Eich. Within the space of a few years he had erected several ironworks. The first steam engines arrived, followed by a blast furnace equipped with the first blowing machine in the country - manufactured by the famous Belgian firm, Cockerill.

In 1869 mining began at the major iron ore deposits in Fond-de-Gras on the southwest border of the country. Collieries were set up, above all by Belgian firms, and the quiet villages in the valley of the River Korn were transformed into working class housing estates. A new railway line was built to transport the ore to the French border.

Blast furnaces sprung up in the surrounding district. Norbert Metz, in particular, the brother of the industrial pioneer Auguste Metz, erected new ironworks in Esch. The flourishing business was further boosted in 1879 with the patenting of an improved process for exploiting "Minette" ore – there were rich deposits in South Luxemburg and Lorraine - which was rich in phosphorus. Norbert Metz was the first person on the continent to be given a licence for Bessemer steelmaking.

Most of the coke for the blast furnaces in Luxemburg came from Germany. On the other hand the iron and steel produced here was sent to the Ruhrgebiet for further processing. The dependency on Germany was also clear from the fact that, at the start of the 20th century, the second largest steel concern in Germany was the first company to build an integrated ironworks with a blast furnace, steelworks and rolling mill in Esch. In 1911 Norbert Metz’ group of companies merged with another Luxemburg steel manufacturer under the joint name of "Aciéries Réunies de Burbach-Eich-Dudelange" ("Arbed" for short) – a major European concern now known as "Arcelor-Mittal". At the time Luxemburg was one of the ten largest iron and steel manufacturing countries in the world.