ON THE INDUSTRIAL HISTORY OF SLOVAKIA

Though Slovakia has a long mining tradition, it remained an agricultural nation until well into the 20th century. The late Middle Ages was the golden age of Slovakian mining: gold, silver and copper from mines throughout the Slovak Ore Mountains guaranteed the power and wealth of the Hungarian kings, who ruled Slovakia until 1918. In that era, cities such as Banská Štiavnica, where pre-Christian Celtic peoples mined precious metals, and the “Golden City” of Kremnica, whose historical mint is still in operation today, flourished. In the 14th century, Rožňava was elevated to the rank of city on account of its gold, silver and copper mines; later, the city enjoyed a renaissance driven by iron mining. The importance of the mining region gradually declined from the start of the 16th century due to increasing technical problems in the mines and competition from South American precious metals.

In the mid-16th century, Hungary became part of the Habsburg Empire, and the monarchs in Vienna used their new domains mainly to supply food for the empire. Mountainous, poorly accessible Slovakia sank into poverty. The mining tradition, however, lived on: in the 18th century, Maria Theresia established a mining academy in Banská Štiavnica, and Slovakian mines were still delivering a large part of Hungary’s demand for precious metals and iron ore into the 19th century. Numerous small iron works thrived at the edges of the Ore Mountains, mostly operated by nobles such as the Andrássy or Kohary families. However, as all the prerequisites for industrialisation were lacking and the agricultural sector was extremely backward, the result was massive labour migration and emigration.

The first railway line, from Bratislava to nearby Svätý Jur, opened in 1840 and soon extended to Vienna. Budapest was connected in 1850, and in 1872 trains were crossing the country from Košice in the east to the Czech town of Bohumín. Scheduled passenger and freight services developed on the Danube. Thanks to its location on the river and its proximity to the metropolis of Vienna, Bratislava gradually developed into an urban centre with industrial operations.

When Czechoslovakia was founded in 1918, its backwardness compared to highly industrialised Bohemia was dramatic, and did not diminish in the following years. The new borders severed Slovakia from its established markets in Hungary, and a half-hearted land reform failed to give Slovakian farmers access to fertile land. When Germany annexed the Czech part of the republic in 1939, a nominally independent “Slovak state” was established, which was soon integrated into the Nazi arms production through German capital. Many old iron works were expanded into major steel plants, and the Skoda arms factory in Dubnica was transformed into a giant production centre for artillery, munitions and heavy weapons. Germany modernised roads and railway lines for strategic purposes.

The path to industrialisation dictated by Germany was continued under Soviet aegis after Czechoslovakia was reconstituted in 1945. In the course of establishing powerful heavy industries in the new socialist nations, the leadership of the USSR assigned Slovakia the role of arms maker. The existing armaments factories continued to operate, joined by gigantic new complexes like the VSŽ steel works at Košice, for which iron ore had to be imported from the Soviet Union and coal from Czechia. The heavy machinery combine ZT’S was established in the city of Martin on the periphery of the Lower Tatra to take advantage of the labour surplus in this agricultural region. The largest employer in Slovakia, ZT’S manufactured locomotives and tractors, as well as T-series tanks under Soviet license.

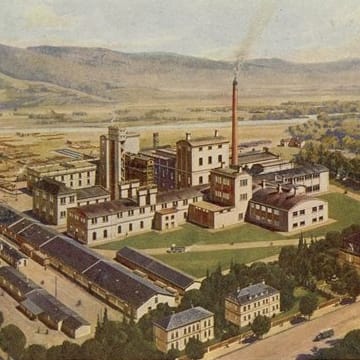

The central state planning systematically promoted Slovakia’s development in order to reduce ethnic tensions and the economic lag behind the Czech part of the country. In addition to the steel industry, dominated by the military, and machinery, this policy established chemical plants, cellulose and paper factories and other operations. The University of Bratislava, founded in 1914, was expanded, and new institutes of higher education were established in Košice, the second largest urban centre, as well as in smaller cities. The successful industrialisation led to urbanisation of the traditional agrarian society. As in the other socialist countries, the high growth rates were achieved at the cost of steadily increasing resource consumption and massive restrictions on the supply of ordinary goods for the population.