ON THE HISTORY OF THE SERVICE AND LEISURE INDUSTRY

The Industrial Revolution resulted in more and more smokestacks shooting out of the ground and a huge increase in factories, coal mines and steelworks; villages merged into towns, and sleepy hamlets were transformed into booming cities. For the first time trading, administrative and leisure facilities had to be organised for masses of customers in new, heavily populated centres.

The precursor of the huge department stores was "Les Halles", the huge and legendary market halls in Paris which were built in the middle of the 19th century. The town planner, Georges-Eugène Haussmann, who radically modernised the mediaeval building structures of the French capital, expressly requested that they be built of glass and prefabricated iron segments in accordance with the time. A little later, the first major department stores like "Les Magasins du Printemps" opened. Here an iron skeleton replaced walls as the major supporting structure in the building. This also allowed sales spaces to be more flexibly designed. Typical features included glass-roofed inner courtyards with galleries, and curving staircases in the middle of the rooms.

At the start of the 19th-century the majority of products in the upper price ranges were sold in so-called passages. These were lines of shops in a glass-covered gallery, at first in Paris and London and later in Brussels, Berlin and other major cities. Around the turn of the 20th century, the splendid "Galleria Vittorio Emanuele" in Milan inspired the German entrepreneur Leonard Tietz to copy his model in Berlin and Dusseldorf, where he built department stores with impressive facades containing large areas of windows.

Around the same time architects like the Austrian, Otto Wagner, began to design public buildings in an objective and functional manner. The Savings Bank Office in Vienna, built by Wagner between 1904 and 1912, has become a milestone in the history of architecture. Since the owner demanded "maximum solidity" the facade was clad with precious marble: that said, Wagner left the assembly bolts visible for all to see. The form of the building was determined by the functions performed within it.

The American Louis Sullivan summed up this basic principle of modern architecture with the pithy formula: "form follows function". Sullivan had a major influence on the style of the new office blocks that began to be built in major cities at the end of the 19th century, above all in the USA, because leading companies needed increasingly larger administration sections to market mass products. Office work was a dynamic new service sector, and in the United States it triggered off countless new techniques. In 1876, the American Alexander Graham Bell constructed the first marketable telephone, and in the 1880s the Remington company launched the typewriter on to the market.

New office buildings were particularly prominent in Chicago. By building skyscrapers it was possible to exploit expensive real estate in the city centre in an optimal manner. The safety lift, developed by Elisha Graves Otis in the mid-19th century, ensured that people could be reliably transported to the top floors, because it was equipped with an automatic braking system which went into action if the cable broke. Iron skeleton frames soon took over from bricks as the major support structures for skyscrapers; here the supporting structures were coated with terracotta or cement as a protection against fire. Facades were mainly structured by large windows and – with the exception of an eye-catching ground floor –were uniformly designed from top to bottom to enable as many similar storeys to be piled up on top of one another, as one wished.

As work became ever more mechanised during the industrial age, manufacturers increased working hours, without heed to the increasing stress on men, women and children who were operating the machines. Things only began to change around the 1870s, when the working week was reduced to around 70 hours, mainly as a result of pressure from the unions: this had sunk even further to around 50 hours by the First World War. Increasing leisure in the evenings, and soon on work-free Sundays, meant that a huge variety of new forms of entertainment sprung up in heavily populated cities.

The forerunners in France, from around the middle of the 19th century, were the large permanent circus halls. In Paris the "Cirque d’Hiver" was built right on the Champs Elysées, and the "Cirque Napoléon" was constructed with a glass and iron dome. Smaller towns also had their own "hippodrome", as the halls were often called, where spectacular horse shows, circus shows and operatic performances took place: there were even water battles as in the ancient Roman circuses. That said, the fate of the "Hippodrome du Champ de Mars" in Paris in 1911 was typical for the 20th century: it was rebuilt and opened as the "Gaumont Palace", the largest and – after further extensions - allegedly the most impressive cinema palace in the world.

Public film shows started in Paris in 1895 and quickly became the leading mass medium. The over-decorated facades of the first cinema buildings, which were built around 1910 in many towns, showed that films were at first regarded as a form of fairground attraction. But soon the architects were striving to build neoclassical buildings with luxurious equipment in order to give the cinemas an impression of respectability. The boom years of film theatres followed in the 1920s, when – principally in the USA – glittering dream palaces were built, like the art-déco "Radio City Music Hall" in New York and "Graumann’s Chinese Theater" in Hollywood. The new objective style of building was most predominant on mainland Europe, even in cinemas like the monumental "Lichtburg" in Essen and the "Universum" in Berlin, built by the famous architect, Erich Mendelsohn.

Pleasure parks in European capitals have an even longer tradition. They flourished in the 19th century. In London, "Vauxhall Gardens" even existed since the mid-17th century. This was a respectable park with shaded walkways and fountains: later additions included concert pavilions and restaurants. Illuminations and firework shows were also presented there. The "Prater" in Vienna developed in a similar fashion. It was originally an imperial wild game reservation, but in the mid-18th century it was opened as a public municipal park. It was not long before it was equipped with bowling greens and roundabouts. The famous Big Wheel was built for the World Exhibition of 1897. By contrast the "Tivoli Gardens" in Copenhagen, based on London parks and built in 1843, were equipped from the start with exotic buildings, concert stages and fairground rides.

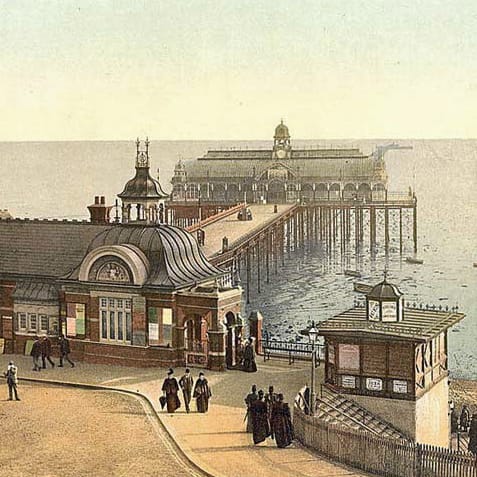

At the end of the 19th century seaside piers began to spring up in British coastal resorts – a national peculiarity. They developed from landing stages and stretched out into the sea to enable walkers to enjoy the water and sea air even at low tide. Competition between the various seaside resorts triggered off further investment and soon pleasure piers became one of the main characteristics of the Victorian époque. Soon visitors were passing through representative arched gateways to restaurants and music halls, many of them decorated in an oriental style with onion-shaped cupolas, towers and cast-iron decorations. Other attractions offered on piers included orchestral concerts, ice-skating and penny-slot machines; all of them just a few metres above the waves.