ON THE HISTORY OF PRODUCTION AND MANUFACTURING

Domestic handmade textile production was typical for the pre-industrial age. The father sat at the loom and the women of the family were responsible for spinning the yarn. An entrepreneur (in Germany he was called a "Verleger") delivered the raw material and organised sales, often over considerable distances. Textile manufacture was the leading industry in Europe: from the 16th century onwards it was basically organised on such a system.

The first types of factories grew up in the 17th century, when larger groups of workers were concentrated in so-called "manufactories". Although this also applied to textiles, it was more common in glass and salt production, ironworks and hammer works. In France, Royal manufactories produced tapestries, furniture and porcelain in magnificent style. The process was divided up into sections from the start, and the workers had to keep to a strict discipline despite the fact that the majority were still working individually by hand. The decisive element which turned the whole world of work on its head was mechanisation.

The factory age began around the end of the 18th century in Britain, with large spinning mills in the county of Lancashire. Here one waterwheel was able to drive around 1000 spindles. Shortly afterwards there followed the steam engine, which made production independent of swiftly flowing water and gave a huge boost to mechanical spinning, weaving and, soon after, the whole of the British economy.

From now on machines dictated the organisation and tempo of work: but not only in textile manufacturing. The Economist, Adam Smith, tells of a factory where the manufacture of a pin was divided up into 18 working sections. In 1769, the English pioneer, Josiah Wedgwood, opened up his porcelain factory "Etruria" near Stoke-on-Trent. Whereas before that, workers had followed the path of their product from the pottery wheel to decorating, firing and storing, they were now ordered to keep strictly to their own department.

Division of labour raised productivity considerably. The actions of the workers, on the other hand, were increasingly reduced to a few, constantly repeated movements. As a result they gradually became alienated from the products they made. Formerly their products had been the pride of hand workers. Since expert knowledge was hardly necessary, employers now preferred to employ women and children whom they could pay less than men. The workers were ruthlessly exploited. Women and children in textile factories had to work shifts of between 14 and 16 hours. Even hen working conditions improved during the course of the 19th century – primarily for children – this tendency was aggravated even more by the introduction of mass production.

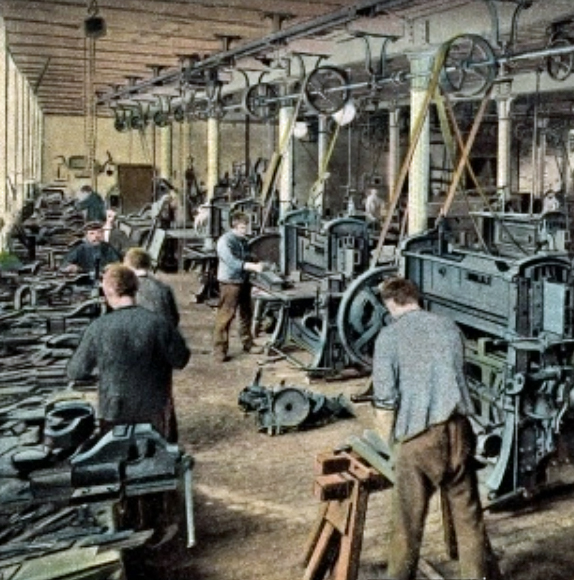

As early as 1797 an American by the name of Eli Whitney suggested making rifle locks from exchangeable parts, instead of making them individually for every weapon. Thanks to this standardisation – a basic prerequisite for mass production - costs were drastically reduced and production further accelerated. The manufacture of exchangeable parts only really came to the fore at the end of the 19th century with the arrival of new metal precision tools. After that, the production of standard quality tools gradually became a manufacturing branch in its own right: machine tool manufacturing.

In 1881 in the USA, Frederick W. Taylor began to divide working processes systematically into their smallest components, in order to rationalise them even more. His quantitative analyses laid the foundations for "Taylorism": scientific production management. The immediate results were that engineers would go round the factories checking working processes with a watch in their hand in order to speed up the work.

The last stage of mass production was the introduction of the conveyor belt. This began in the stockyards of Chicago and Cincinnati. It was then adapted by Henry Ford in 1911 for his motor car factories in Manchester and Detroit. Whilst the conveyor belt was moving forward the next chassis at a constant speed the workers had to mount the components with as few actions as possible to avoid any "unproductive" movements. The pace of production was even more drastically increased. Whereas it had formerly taken 12.5 man-hours to mount a chassis, by 1914 only 93 man-minutes were needed. Thus Ford cars could be afforded by everyone.

In the second half of the 19th century methods of industrial production reached the food sector. The powerful engines which delivered energy independent of the specific location, encouraged entrepreneurs to set up large bakeries and breweries. New techniques made the processing of agrarian products increasingly independent of the seasons of the year.

The invention of artificial cooling methods was an important step. In 1748 a Scotsman by the name of William Cullen was the first man to demonstrate how to extract warmth from the environment by reducing a fluid to steam. The process was made even more effective by compressing the refrigerating agents. That said, it was quite a long time before these principles could be used to make the first effective refrigerator. An American by the name of Jacob Perkins is reputed to have built the first model in 1835. Around 20 years later an Australian, James Harrison, introduced refrigerators to the meat and brewing industries.

Thus large-scale beer production became possible during the summer months. At the same time people learnt how to control the temperature of the mash with a thermometer, and the amount of original gravity with a saccharometer. Such scientific knowledge was characteristic for the whole area of food production.

Conservation was a further step. The fact that food remains edible when it is kept in a closed container at a certain temperature over a long period of time, was discovered by a Frenchman, Nicolas Appert, in 1809 when he was charged with supplying food to Napoleon's armies. His British colleague, Peter Durand, discovered that tins were the best containers for doing so. But it was not until 1863 that a scientist by the name of Louis Pasteur discovered that microbes could be killed by heating. The production of tinned food spread quickly, most of all in the USA, and the United States soon became the market leader.

Milk conservation can also be traced back to military requirements. During the American Civil War in the 1860s Gail Borden developed condensed milk. A Swiss firm launched it onto the European market and soon after it merged with another firm owned by Henri Nestlé, the inventor of baby food. The result was that condensed milk became famous under Nestlé’s name.

Around the end of the 19th century a new form of co-operative manufacturing arose in dairy production. Dairy farmers, above all in the Netherlands, Scandinavia and northern Germany, joined forces to market their dairy produce. Cooperative dairies produced butter and cheese to uniform standards and conquered ever larger markets beyond national boundaries. The standardisation of food production, increasingly independent of the time of manufacture and the region where it was made, has continued right down to the present day.