ON THE INDUSTRIAL HISTORY OF ALBANIA

Albania’s economic history is characterised by a fundamental contradiction: the country has valuable natural resources, fertile soil and enormous hydroelectric potential, yet has remained one of Europe’s poorest regions for thousands of years.

Bitumen was mined in Selenica even in ancient times, when it was valued primarily as a sealant. The port of Durrës was the starting point of the Via Egnatia, a major transit route across the Balkans to Constantinople. Trade continued to flourish under the Ottomans, who conquered Albania towards the end of the 15th century, now centred in the cities of Elbasan, Shkodra and once again Durrës. Agriculture, however, stagnated for over four hundred years. The fertile fields were held by predominantly Moslem large landholders who had no interest in modernisation or market production, while the peasants in the mountains with their tiny plots were barely subsisting.

When Albania declared independence in 1912, the country was significantly underdeveloped and had virtually no roads or railways. Education levels were extremely low. Following World War I, Italian companies began extracting petroleum; beyond that, industry consisted of a handful of factories for producing foods and processing cotton, tobacco and wood. The agricultural reform of President Ahmet Zogu, who crowned himself king in 1928, was a failure. The peasants – who were still using wooden ploughs – were unable to feed the rapidly growing population. At the beginning of the 1930s, around three quarters of Albania’s children were still illiterate. Mining of coal, copper and chromite ore gradually commenced, driven mostly by Italian companies. The state’s budget soon became dependent on Italy.

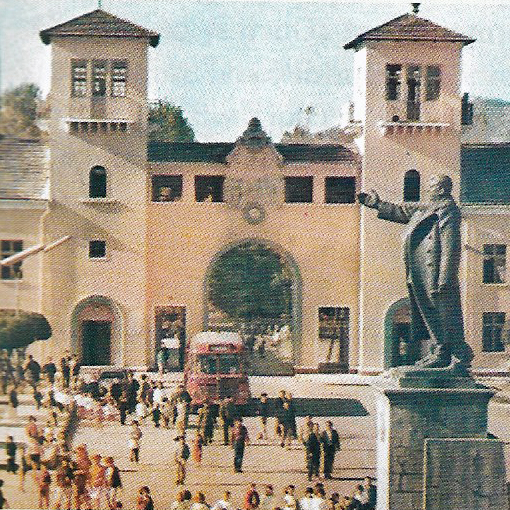

The government of the Socialist People’s Republic of Albania, proclaimed in 1944, sought economic support from its neighbour Yugoslavia and assumed the Soviet Union’s economic model. Landholdings and businesses were nationalised, heavy industry was massively expanded. The first train went into service between Durrës and Pequin in 1947, and a rail network emerged over the following decades. However, the lines were constructed primarily by poorly qualified soldiers and youths in “voluntary work missions” and did not permit higher speeds, while the carriages and locomotives were purchased used from abroad.

Following Yugoslavia’s break with the Soviet Union in 1948, the Albanian government turned to Moscow for support. Russian financial aid flowed into the country, and Russian specialists helped out with projects such as completion of the first hydroelectric plant in Selita. As the Soviet Union and its allies proved to be grateful buyers of Albanian raw materials, exploitation of petroleum, copper, chrome and bitumen boomed. Agriculture, however, continued to be neglected, so that Albania was frequently forced to import large quantities of grain. At the same time, it grew increasingly indebted to the USSR.

In 1961, dictator Enver Hoxha broke with the Soviets and sought assistance from Moscow’s “competition” in Beijing. Albania’s economy continued to expand thanks to Chinese support. Raw materials were now increasingly being processed domestically: copper at the Shkodra cable and wire plant and petroleum in one of the first Albanian refineries in Fier. The nickel-infused iron ore from the Pogradec region went mostly to the iron and steel plant at Elbasan, the nation’s largest. In 1970, the government proudly declared that it had connected the entire country to the electrical grid, thanks to new hydroelectric plants.

It is believed that this is when the industrial proportion of economic output exceeded that of agriculture – although the statistics do not offer any reliable data. However, it rapidly became apparent that the now relatively modern and varied industrial base was not viable without subsidies. When the Chinese government cut off its aid in 1978, Hoxha declared that the nation would refuse all foreign aid and proclaimed his vision of a self-sufficient Albania. Soon after, production began to decline inexorably, a process that at the start of the 1990s ended in a national collapse with looting, starvation and disorder.