ON THE INDUSTRIAL HISTORY OF SWEDEN

Sweden’s long road to becoming an industrial nation followed a familiar path in that the process began with agricultural surpluses and a consequent population growth. However, development was also influenced by some specifically Swedish factors: far-sighted state intervention and large-scale exports of the plentiful raw materials of iron ore and wood. By contrast, Sweden has very few coal deposits.

Until the end of the 17th century, copper from the long-established mine in Falun also played an important role: it enabled Sweden to finance its bid to become a major power. The earliest signs of a nascent industrial revolution appeared in the first half of the 18th century: entrepreneur Jonas Alströmer founded a partially mechanised textile factory in Alingsås, and the polymath engineer Mårten Triewald erected the first steam engine at the iron mine in Dannemora. However, both enterprises failed and Sweden remained a poor, agrarian country for a long time.

At the start of the 19th century, widespread modernisation of agriculture led to an initial economic upswing and a growth in population. However, it was policy decisions that laid the foundation for Sweden’s eventual prosperity: after losing its dominion over Finland in 1809, Sweden surrendered all dreams of great-power status. The national borders have not changed since 1815. The Swedish Army was assigned to the construction of the Göta Canal, which extended from the North Sea at Gothenburg across Sweden to the Baltic – it was regarded as a symbol of national efficiency. The canal was not an economic success as it was quickly made redundant by the arrival of the railways. A state railroad construction programme was launched, and the main lines from Stockholm to Malmo in the south and Gothenburg in the west opened in 1864. By the start of the 20th century links had been constructed to the north, including the ore railway from Luleå to Narvik in Norway, which connected the mines to both the Baltic and the Atlantic.

Education policy also played an important role: complementing the traditional universities in Lund and Uppsala, the polytechnic "Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan", today called the Royal Institute of Technology, was founded in Stockholm in 1827. Sweden introduced compulsory schooling in 1842.

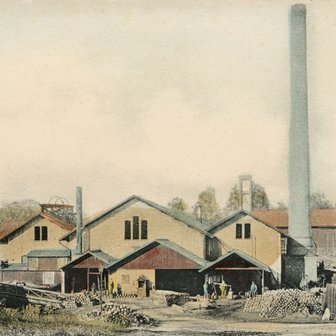

An export boom commenced around the mid-19th century that lasted, with interruptions, for around a hundred years. England’s expanding industries in particular purchased enormous quantities of raw materials: wood from the north, iron from central Sweden and oats as horse feed from the still-predominant agricultural regions. Investments had to be financed largely by foreign capital, but the economy continued to grow and increasing domestic demand also drove mechanisation of the textile industry, particularly in the region centred on Borås and the expanding industrial city of Norrköping.

Towards the end of the century, Sweden profited greatly from the Second Industrial Revolution, in which new sectors outgrew heavy industry, including energy, chemical and machine-tool industries and wood-based paper manufacturing. Fed by the country’s enormous hydroelectric potential, a flourishing electrical industry emerged, led by the company Allmänna Svenska Elektriska Aktiebolaget, or ASEA for short, and now called ABB. Swedish successes in this invention-rich era included new forms of ball bearings, which formed the basis for the enterprise Svenksa Kugellagerfabriken, or SKF. The telephone manufacturer Ericsson was also founded in this era: Lars Magnus Ericsson opened his first shop in Stockholm in 1876 – the same year in which Alexander Graham Bell patented his telephone in the USA – and in 1885 Stockholm had the most telephones in the world.

Sweden secured its status as a leading industrial nation in the first half of the 20th century. During the First World War, Sweden’s unhindered industries supplied all parties, particularly with steel, and was able to demand grossly inflated prices. This enabled the country, which was notoriously dependent on foreign capital, to get its debt under control. When Europe’s markets were plunged into crisis at the end of the war, the newly available investment capital stabilised the Swedish economy by supporting domestic demand. An automotive industry now emerged with the companies Scania, Vabis and Volvo, followed by Saab after the Second World War. In the economic boom after 1945, the Swedish Model, in which the state directs the labour and capital markets with the aim of promoting a productive, prosperous society, reached its zenith.