ON THE INDUSTRIAL HISTORY OF ANDORRA

The Principality of Andorra boasts a unique economic history. On account of its inaccessible location high in the Pyrenees, far from any trade routes, and with only a limited amount of farmland, it remained for centuries an overlooked, poverty-stricken country with a feudal social structure – yet today it is one of Europe’s most prosperous nations.

Andorra was recognised as an independent state in 1278, but it was ruled by two foreign “co-princes”: The Bishop of La Seu d’Urgell – the Catalonian city to the south – and the Count of Foix to the north of the mountains, whose rights fell to the French crown in the 16th century. In 1532, Andorra was granted freedom from customs duties.

Until well into modern times, economic activity consisted mainly of sheep-rearing and forestry. Starting in the 17th century, this was augmented by a handful of forges that smelted the locally mined iron ore. The charcoal-fired Catalan forge was long considered particularly efficient, and was in common use in Andorra until well into the 19th century, long after the blast furnace had become the standard method of smelting in the neighbouring countries.

The economy was dominated by a handful of aristocratic families, some of whom have preserved their influence down to the present day. As early as 1619, the House of Rossell owned the largest forges. One of the family’s progenitors was the jurist Antoni Fiter i Rossell, who is considered the country’s first literary figure. The Rossel Forge, which opened in the 1840s and closed in 1876 when the Andorran iron mines ceased production , is today a museum.

The Areny family has also been active in the iron business since the 17th century. The family estate in the town of Ordino is today open to the public as an example of an aristocratic manor house. In the 19th century, the entrepreneur Guillem d‘Areny-Plandolit was also an active merchant and banker. He also played an important role in the reforms of 1866 that granted the common people a modest political role for the first time. His son Pau Xavier founded Andorra’s first, albeit short-lived, museum in Ordino in 1903.

Tobacco farming emerged as a further important industry at the end of the 17th century, not least on account of the profits to be made by smuggling cigarettes into Spain. The museum housed in the tobacco factory founded by the Reig family, which operated from 1903 to 1957, testifies to this history. It is characteristic of the structure of Andorra’s economy that Julià Reig i Ribó, a son of the founder, also launched a bank and a real estate enterprise in the 1950s. In the latter half of the 20th century a number of the country’s heads of government came from the family.

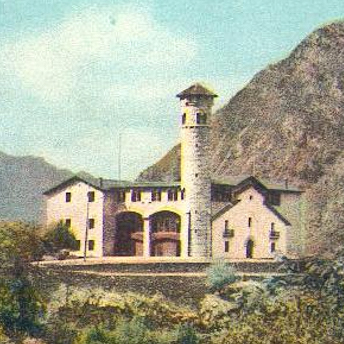

Andorra tentatively began to open up in the first half of the 20th century, when the first roads to Spain and France were constructed. Even today, the country is entirely without a railway link. An economic renaissance was eventually sparked by the construction of a hydroelectric plant at Engolasters Lake, which began operation in 1934. It still supplies most of the country’s electricity, but also serves as a museum. Labour had to be recruited from Spain for its construction, roads were built, banks and department stores were founded.

From the 1950s on, development acquired a momentum all its own. Further financial institutions opened their doors, and the construction of the first ski lift in 1957 signalled the arrival of a booming new industry: tourism. Fuelled by a virtually complete exemption from customs duties and low taxes, the economic sectors of retail, real estate and banking – the latter long under suspicion of money laundering – now form three additional pillars of one of Europe’s richest economies. In this way, Andorra, which did not transition from a feudal country to a parliamentary system until 1993, managed to make the leap from an extremely impoverished agricultural backwater to a flourishing service economy without the intermediate step of industrialisation.