European Themeroute | Chemistry

The emergence of the chemical industry was triggered by the mechanisation of English textile production in the second half of the 18th century. The output of the new spinning and weaving machines increased rapidly, and manufacturers needed new chemicals to clean and bleach the vast quantities of linen ... more

Chemistry

Chemistry

The emergence of the chemical industry was triggered by the mechanisation of English textile production in the second half of the 18th century. The output of the new spinning and weaving machines increased rapidly, and manufacturers needed new chemicals to clean and bleach the vast quantities of linen and cotton fabrics. Three substances rose to prominence: sulphuric acid, soda and chlorine. However, their closely related production processes caused serious damage to nature and human health.

Traditionally, sulphur was leached from shale and burned to produce sulphuric acid: the acid vapours were collected in vessels with water and distilled. In 1746, the English entrepreneur John Roebuck introduced lead chambers to collect the vapours. Production could now easily be increased by enlarging the chambers, and sulphuric acid became the first industrial chemical. Factories supplied acid mainly for pickling metals until demand exploded for bleaching linen and cotton. By the beginning of the 19th century, the first continuous manufacturing process was in place - a prerequisite for large-scale industrial chemical production.

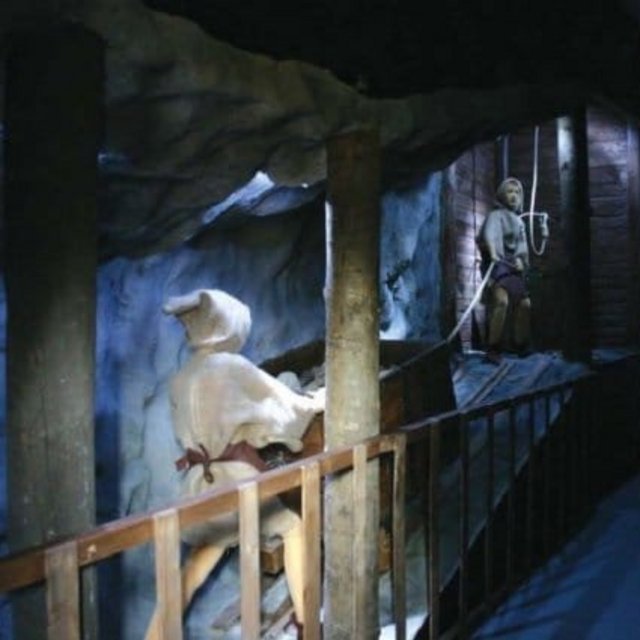

Soda, chemically "sodium carbonate", was also used for bleaching, but was also a basic material for the production of glass and soap, which was also needed for textile processing. For a long time it was produced according to a principle patented by the French chemist Nicolas Leblanc in 1791: sulphuric acid and salt were heated in a furnace, the resulting "salt cake" was roasted together with lime and coal, and the water-soluble soda was then washed out of the "black ash". The process made cotton goods and glass much cheaper, but released many highly toxic by-products.

Chlorine also became an industrial product early on, thanks to its ability to bleach textiles - including rags used in paper production. The first effective bleaching agent was produced by a French factory in 1789: chlorine was added to a lye of potassium carbonate to produce "chlorine water". A few years later, the Scottish chemist Charles Macintosh discovered that chlorine gas was absorbed by slaked lime: This made a bleaching powder available - practical for industrial use, but extremely harmful to health in production.

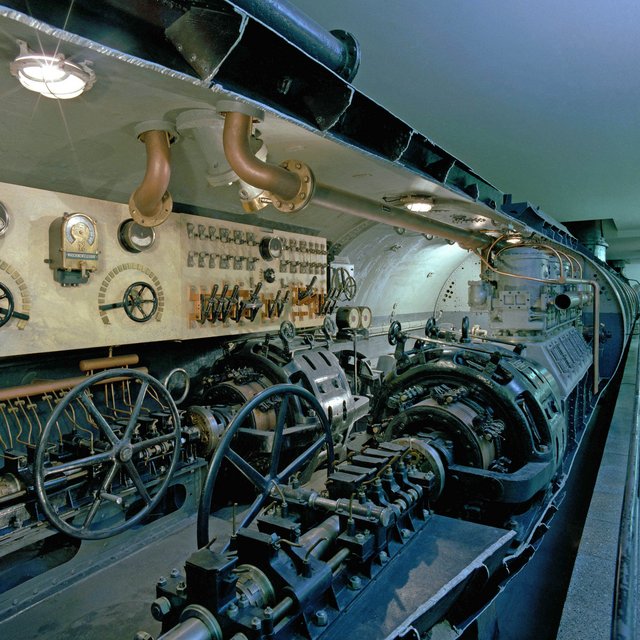

Since its discovery in 1709, coke has been used in the iron industry for its high calorific value - and at the turn of the 19th century, a by-product of coking gave rise to a new branch of chemistry: coal gas. From 1807, gas lighting became widespread in England. First in textile mills, which produced gas on site from coal, then for street lighting: cities built huge cylindrical gas tanks in central gas works, from which "town gas" was distributed through cast-iron pipe networks. Later, long-distance pipelines from coal-rich regions were also used.

In the second half of the 19th century, during the "second industrial revolution", chemistry became the leading industrial sector alongside electrical engineering. One reason for this was that researchers were able to identify active ingredients with increasing precision. As early as the 1840s, John Bennet Lawes in England and Justus Liebig in Germany had identified the substances on which plant growth depended: Once nitrogen, potassium salt and phosphorus had been identified, it was possible to increase agricultural yields with artificially produced substances - and for the first time in history to establish secure food production independent of the weather.

On the other hand, theorists had gained insights into the structure of chemical elements: The "structural formula" developed by Friedrich August Kekulé - the most famous example being the benzene ring - made it possible to describe the composition of countless chemical compounds, thus simplifying their artificial production, or "synthesis". Chemistry took on a new face. From now on, science played a central role, as analyses were mostly carried out in university laboratories before the rapidly expanding industry could synthesise the active ingredients.

Now a second by-product of coal coking came into play: Researchers identified active substances in coal tar that could be used to synthesise dyes and, soon, medicines. In 1856, the Briton William Henry Perkin produced violet from the aniline extracted from the tar. Soon after, artificial indigo blue was made, also from aniline, and then red from madder, the root of dyeing red, was replaced by alizarin. These two dyes were developed by the Badische Anilin- und Soda-Fabrik (BASF), one of the three German chemical companies founded in the 1860s, along with Hoechst and Bayer, which overtook the English companies as the world's leading tar-dye-based corporations.

When it became apparent that paints also contained therapeutic agents, companies developed the production of medicines as a second mainstay. Initially, antiseptics were synthesised from germicidal substances, followed by antipyretics. New discoveries by bacteriologists such as Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch soon led to the development of vaccines, and by the end of the century Hoechst and Bayer had achieved unprecedented sales with the painkillers Pyramidon and Aspirin.

The basic substances established in the 18th century continued to be produced using improved processes. The Belgian Ernest Solvay revolutionised the production of soda ash in the 1860s. In a production process based on common salt, lime and ammonia, he used solutions rather than solids and lower temperatures than the established Leblanc process. In addition to using less energy, Solvay achieved two advances that would characterise the development of the chemical industry: The process was continuous and could largely be run in a cycle - in particular, the expensive and toxic ammonia was largely reused. The company named after the inventor still produces much of the world's soda ash using the same principle.

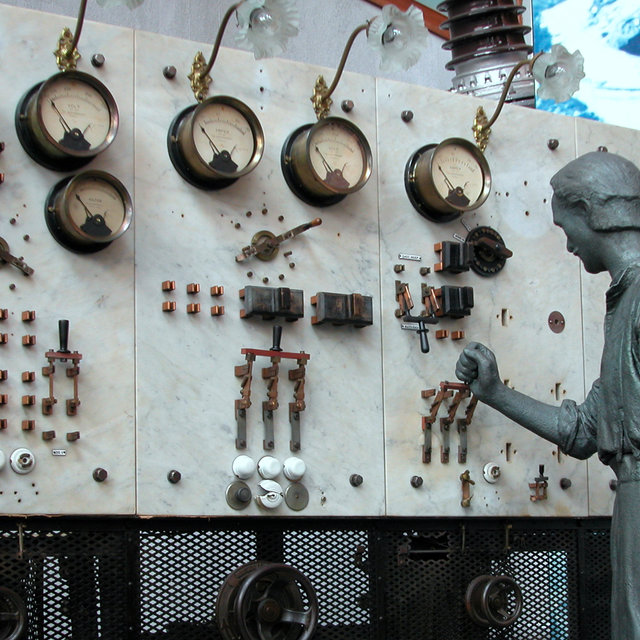

In the 1880s, rapid advances in electrical engineering made electricity cheaper and more attractive as an energy source for the burgeoning electrochemical industry. Electrolysis uses electricity to break down chemical compounds - the American chemist Charles Hall and the Frenchman Paul Héroult produced aluminium from aluminium oxide in 1886. Chlorine could be produced so efficiently that traditional bleaching powder came under massive price pressure. Electrothermics, on the other hand, used heat mainly to operate the new, extremely hot electric arc furnaces that produced steel alloys and carbide for acetylene lamps.

The last major development of this era was in fertiliser production. Since it was known that plants needed nitrogen, potassium salt and phosphates in certain proportions, numerous fertiliser factories had sprung up, and famines caused by weather fluctuations in the rich regions of the world could be put to an end. In Germany, however, there was a shortage of nitrogenous fertilisers until the chemist Fritz Haber succeeded in synthesising ammonia from hydrogen and atmospheric nitrogen in 1909. His colleague Carl Bosch then developed an industrial process at BASF to produce nitrogen fertiliser. Ammonia synthesis" was ready for use in 1913 and is still the most important process for fertiliser production today. At the same time, it is the most striking example of the two sides of chemistry: it helped to alleviate hunger, but was first used to make explosives - without which the German Empire would probably have been forced to surrender at the beginning of the First World War for lack of ammunition.

ERIH Anchor Points

German Technical Museum

Trebbiner Strasse 9

10963

Berlin, Germany

Industry and Filmmuseum

Chemiepark Bitterfeld-Wolfen

Areal A

Bunsenstr. 4

06766

Bitterfeld-Wolfen, Germany

Museum of Work

Wiesendamm 3

22305

Hamburg, Germany

National Museum of Science and Technology of Catalonia

Museu Nacional de la Ciència i la Tècnica de Catalunya (MNACTEC)

Rambla d’Ègara 270

08221

Terrassa, Spain

Member Sites ERIH Association

Nicéphore Niépce Mansion Museum

Musée Maison Nicéphore Niépce

2 rue Nicéphore Niépce

71240

Saint-Loup-de-Varennes, France

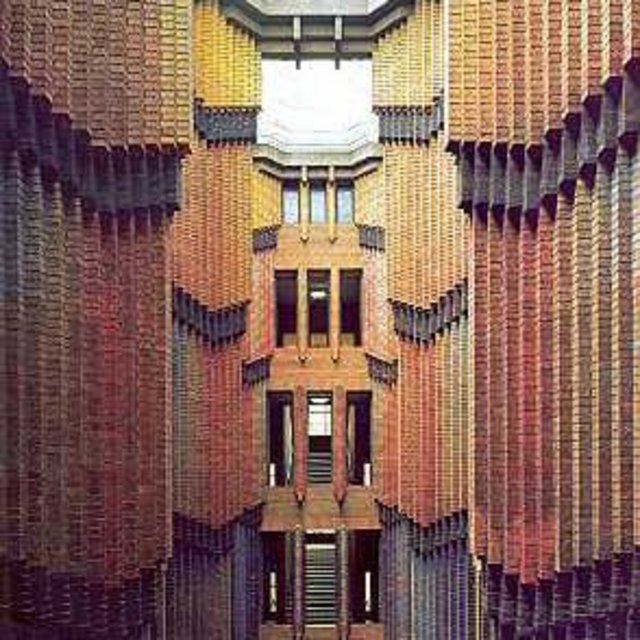

Poelzig Building, former IG-Farbenhaus

Norbert-Wollheim-Platz 1

60323

Frankfurt am Main, Germany

German Chemistry Museum Merseburg

Rudolf-Bahro-Straße 11

06217

Merseburg, Germany

Schönebeck/Elbe Museum of Industry and Art

Erlebniswelt Technik und Innovation (iMUSEt)

Ernst-Thälmann-Straße 5a

39218

Schönebeck/Elbe, Germany

Baía do Tejo Industrial Museum at former Companhia União Fabril (CUF) Area

Museu Industrial Baía do Tejo

Parque Empresarial da Baía do Tejo

2830-314

Barreiro, Portugal

Sites

Villa Petrolea

Nobel Avenue 57/2

1025

Baku, Azerbaijan

National Technical Museum

Národni technické museum

Kostelni 42

17078

Prague, Czech Republic

Muzeum Sokolov

Zamecka 160-1

35601

Sokolov, Czech Republic

The Michelin Adventure

L’Aventure Michelin

32 Rue du Clos Four

63100

Clermont Ferrand, France

Fragonard Perfume Museum

Musée Fragonard

20 Boulevard Fragonard

06130

Grasse, France

Museum of Combs and Plastics

Musee du Peigne et de la Plasturgie

88 Cours de Verdun

01100

Oyonnax, France

Nobel Brothers Batumi Technological Museum

3 Leselidze Street

6001

Batumi, Georgia

Peter Behrens Building

Industrie Park Hoechst

Brüningstraße 45

65929

Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Liebig Museum

Liebigstraße 12

35390

Gießen, Germany

BASF Visitor Center

Carl-Bosch-Straße 38

67063

Ludwigshafen, Germany

TECHNOSEUM. Museum of Technology and Labour

Museumstrasse 1

68165

Mannheim, Germany

Chemical Industry Estate

Ausstellung im Informations-Centrum (IC)

Paul-Baumann-Straße 1

45764

Marl, Germany

Deutsches Museum

Museumsinsel 1

80538

München, Germany

Museum of Chemistry of the Hungarian Museum of Technology and Transport (MMKM)

A Magyar Műszaki és Közlekedési Múzeum (MMKM) Vegyészeti Múzeum

Hunyadi utca 1

8100

Várpalota, Hungary

Ferrania Film Museum

+39 019 50707403

https://www.ferraniafilmmuseum.net

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferrania_Film_Museum

Via Luigi Baccino Ospedale, 28

17014

Cairo Montenotte, Italy

National Museum of Science & Technology – Leonardo da Vinci

museo nazionale della scienza e della tecnologia "leonardo da vinci"

Via S Vittore 21

21023

Milan, Italy

CID Documentary Information Centre Torviscosa

CID Centro Informazione Documentazione Torviscosa

Piazzale Marinotti 1

33050

Torviscosa, Italy

Cobalt Works and Mines

Blaafarveværket og Koboltgruverne

3340

Åmot, Norway

Norwegian Museum of Science and Technology

Norks Teknisk Museum

Kjelsåsveien 143

0491

Oslo, Norway

Nobel Museum in Karlskogs & Bofors Museum

Nobelmuiseet i Karlskoga og Bofors Museet

Björkborns Herrgård

Björkbornsvagen 10

69133

Karlskoga, Sweden

Science Museum

Science Museum

Exhibition Road

South Kensington

SW7 2DD

London, United Kingdom

The Museum of Norwich at the Bridewell

Bridewell Alley

NR2 1AQ

Norwich, United Kingdom

Catalyst

Mersey Road

WA8 ODF

Widnes, United Kingdom